So in the same week I receive news of the new Instagram TV and a new “feature” in Adobe’s Behance portfolio app that allows for sharing “temporary” video. Not one to overlook a cosmic coincidence, I also picked up a paper (quaint, I know) copy of

Samuel Pepys account of the The Great Fire of 1666.

For those who don’t typically read obscure English diarists out of habit, Pepys was a minor bureaucrat and elected official in Seventeenth Century London. His personal journal is a first person account of a good many significant historical events in that city, including the outbreak of the Black Plague in 1665 and the subsequent Great Fire that destroyed a vast area of the city (ironically it also may have brought about the end of the plague).

In fairness, Pepys also recorded a great deal of mundane information such as what he had for dinner, where he went on a given day, the people he spoke with, etc. In short, it’s mostly about the stuff you find today on Facebook and Twitter. In the 1600s, you had to use paper and pen. It is because of this fact that we know the magnificent as well as the mundane from someone who was actually there, whereas otherwise, we might have to wait for “historians” to “conclude” the nature of events based on what records survived. This is why we speak of “dark ages” in human history. We lack a good amount of information because it was either lost or it never existed in the first place.

We stand on the brink of such a dark age. Outside of a handful of writers, artists, cranks, malcontents, and people with tinfoil headgear, the current population of the world has readily accepted storing their thoughts, dreams, ideas, and credit card numbers in possibly the most fragile medium ever conceived by man. We e-mail. We tweet. We skype. Our interactions are ephemeral and our dialogues are diaphanous. When the power goes down or the hard drive crashes, we are gone. There is no “hard copy” to remember us by.

Don’t mistake me for a Luddite. I use the modern technological gadgetry quite a lot. Let’s face it. This article is a prime example of the kind of thing I’m talking about. Unless I print it out, the “publication” is a temporary thing at best. At most it will only last so long as I continue to maintain the website. After that, it returns to the unformed bits from whence it came.

But I’m trying to understand the idea of creating something that is expressly temporary as a means of expression. I refer here to the Behance “Work In Progress” feature that has a lifespan of 24 hours. Why on earth is the visual equivalent of the mayfly something that should interest me, either as viewer or creator?

Part of my quandry is that I suppose this feature to have evolved from the “story” function on Instagram, which as I understood was based upon something native to Snapchat. Full disclosure, I don’t use Snapchat and I’m okay with saying I don’t “get” Snapchat. But as I’m someone who considers finding a discount copy of Samuel Pepys “cool”, I’m fairly sure I’m not the target market, nor are they mine. That said, it was my understanding from general net commentary that Snapchat temp videos were being used for posting “highly personal content”. In that context the temporary nature was a matter of discretion, and that’s fair enough. I did see a couple of webinars trying to pitch me on the idea that this “temp” thing at special event or with an “influencer” created an impression of exclusivity. That is, because it was only there for a short time, you got to be lucky to be a part of it. And apparently that idea was why Instagram came out with a similar but different iteration of temporary visual content.

And yet here we have Instagram TV which now allows up to 10 minutes (read the fine print, the up to an hour is reserved for “influencers” and other verified accounts. We peasants only get 10 minutes for now) of possibly pre-produced video to be uploaded to your branded channel, and as far as I can ascertain, remain there as permanent content. Does this not argue that the disappearing video has not lived up to the value proposition?

I personally have looked at only a couple of the Instagram stories I saw posted, and never went to the trouble of creating one. I simply so no value in taking the time to put together a slideshow or short video when it would just go “poof” in a fixed number of hours. I find this to be an extremely odd idea especially in the context of documenting your artistic creative process, which seems to be the pitch behind Behance’s app addition. If how I do what I do is important enough for me to share, I cannot imagine why I would not want to share it for all time. If Behance is meant to be a professional online portfolio, doesn’t the availability of that information in perpetuity make more sense? Or is this just another attempt to social/gamify the application to keep people interested in paying premium rates.

Which, of course brings us back to Instagram TV, which as many of the reviewers have noted is “advertising free for now“. Everyone can see the writing on the wall, here. Facebook, the owner of the Instagram, has an avowed corporate mission to “sell all that is sellable.” (This is the capitalism manifesto, and one which they can rightly pursue, as far as I’m concerned. I just prefer them being more open about it.) Instagram TV is a means of extending engagement with the Insta brand that is flourishing while Facebook, right or wrong, is experiencing some backlash for their business practices. And of course, it creates more opportunities to play advertising, and at some point institute a pay to play and/or pay per view level of service. (Again, this is business, and the objective is to make a profit, so no moral injunction applies). It’s harder to sell that when your videos vaporize after a couple of days.

The idea of a “temporary” work of art isn’t a new thing. Short term installations, limited run performance pieces, and works built for the sole purpose of being destroyed as part of the “art” have been around since the middle of the last century. The thing that distinguishes most of those “temporary” works is that some part of the experience was “permanently” documented, through a film or a photograph, or a sketch or a script. Something survives in most cases because the artist wanted something preserved.

We should, as artists, always be willing to explore new concepts. But we should also understand that the underlying trend of an expressly vanishing work, may not be a good thing in the long term.

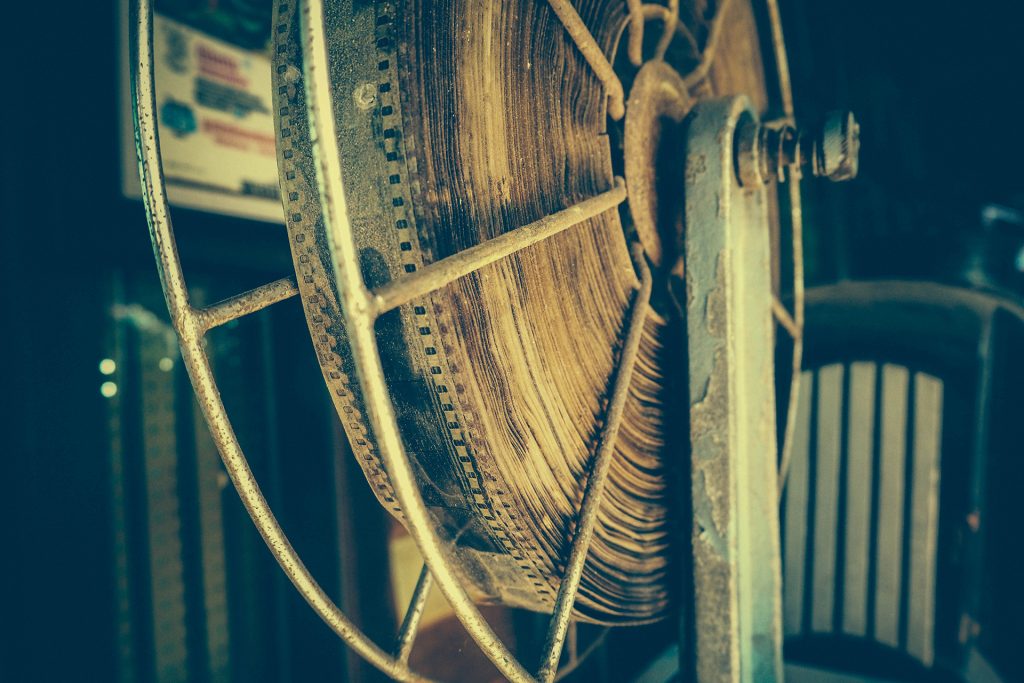

Photo by Fancycrave on Unsplash